| |

SSNS Home > Senior Years > Curricula 9 to 12 > Grade 11 > MAC 1913-14

Manitoba Agricultural College (M.A.C.) Buildings

1913 - 1914

Excited anticipation probably best described the atmosphere at the Manitoba Agricultural College when school opened in the fall of 1913. It permeated the offices of the new administration building, the classrooms scattered across the campus, and the student residence overlooking the Red River nearby. The pastoral beauty of the prairies was everywhere visible, adjacent farms and fields a reminder of the college’s central purpose, although a recently paved Pembina Highway and the street car line connecting the campus to Winnipeg were solid evidence of the urban presence. It was a time of change, not just in the surrounding landscape, but in lives as well. For college staff, it meant relocation from the comforts of the old campus to the unfamiliarity of the new. For the young men and women entering the college for the first time to study Agriculture and Home Economics, it was the beginning of an adventure, possibly the first one away from the home fires of the farm. Life was rich with possibilities, the future bright, the rumble of guns still unheard from across the seas.

In 1913, agriculture was king. It had been steadily growing in importance for well over thirty years, with no end in sight, and prairie farmers were increasingly interested in applying the latest scientific principles in its pursuit. None of this was fully appreciated at the time. Indeed, when the Manitoba Agricultural College opened in the fall of 1906 at the Tuxedo campus, nobody realised that in less than five short years it would have outgrown its facilities. Indeed, by 1911, the dairy barn had been converted into a dormitory, and thirty students were living off campus. With no land available nearby and more and more students clambering to attend, the government realised that a new location for the college had to be found. Eventually it settled on a parcel of land east of Pembina Highway and approximately seven miles south of the city. Consisting of about six hundred acres surrounded on three sides by a loop of the Red River, the site offered plenty of space for present and future growth, and work began in the summer of 1911 to clear the land. By that winter, 375 acres had been cleared and about 125 acres of this had been broken for the test and demonstration field plots required by the college. Construction was also underway on the main buildings. During 1912 and 1913, the work moved ahead at a feverish pace. When the college opened on 28 October 1913, much of the major construction had been completed, certainly enough to commence the school year.

Built at a cost of over 3 million dollars, which was a huge amount of money at the time, the campus was magnificent. Indeed, the centrally located Administration Building radiated a stately grandeur that could not fail to impress the visitor, who approached it for the first time from the road connecting the college to Pembina Highway. Sets of four massive stone pillars and wide stone steps dominated both the eastern and western façades of this building, providing a fittingly frame for the main entrances that opened into a large rotunda dominated by massive marble stairs. Ascending from the level below and rising four stories to a huge dome that diffused light from above through beautiful stained glass, the stairs connected the different levels of this central space, onto which all offices and other rooms in the building opened.

The Administration Building was a focal point for the students. Its lower level housed the post office where they could pick up their mail at general delivery or in a private box. They could also purchase books and other school supplies at the bookstore located there.

The offices of the registrar and bursar were located on the main floor. Students registered here when they entered the college and made arrangements to pay the required fees. They could also deposit money with the bursar in a trust fund, from which they could draw funds on Tuesdays and Fridays. W. J. Black, B.S.A., the President of the College had his office on this floor, too, although students had few occasions to go there. However, they might drop in elsewhere to deliver assignments or discuss course work. The English professor, the professor of Animal Husbandry, and the superintendent of Extension work all had offices on the main floor.

A reading room and library, located in the south wing, provided a place for students to study and do research. A large classroom occupied the north wing, and there was a museum there as well, a place familiar to the student body, even if they didn’t visit it often.

Offices for the departments of Field Husbandry (south wing), and Household Art (north wing) were located on the second floor. The Department of Household Science, a large theatre classroom, and the office of the lecturer in English were located on the third floor. The Board Room, where the meetings of the Board of Directors and the Faculty were held, also occupied the third floor.

The Horticulture and Biology Building occupied the north-east angle of the campus. Horticulture, Entomology, and Forestry were located on the ground floor. The second floor was devoted to Botany and included botanical laboratories, a herbarium, drying and pressing rooms, a class room, and offices for the staff. The Dept of Bacteriology occupied the third floor, where there were three laboratories, an incubation room, culture room, and an animal dissecting room. Green houses were connected to this building as well.

The Chemistry and Physics Building occupied the northwest angle of the campus opposite the Horticulture and Biology Building. Chemistry, soil physics, and general physics were taught in this “absolutely fire proof” building, which had walls of tile and brick, floors of terazzo, “with the exception of the floor in one theatre class room,” and no wood even for the doors and door jambs. It had the “most up-to-date apparatus for the teaching of chemistry, soils, drainage, mathematics, and general physics, including electricity, and magnetism.”

Occupying the south-west corner of the quadrangle was the three-story Engineering Building, a U-shaped structure 153 by 110 feet, each of its two wings 53 by 75 feet with windows on three sides. The south wing on the main floor was the laboratory for traction engineering. Eventually, it would be “equipped with a large number of gasoline and steam engines for instruction purposes, and also with ample apparatus for advanced work in engine testing and other phases of mechanical engineering laboratory work.” Since it had insufficient space for handing both regular student classes and the winter short courses that were so much in demand, the college planned in future to use the north wing for this latter purpose. However, during the winter of 1913-1914, this space was used as the forge shop, and would continue in that use until a separate facility could be constructed nearby. It contained forty-four forges, with a set of bleachers for student seating during the daily demonstration lessons in forge work.

The central section of the Engineering Building contained a classroom and offices to the right of the front entrance. On the left was a concrete laboratory where students learned how to test, mix, and place concrete. Part of its floor space was earthen, so that students could practice making “short lengths of sidewalks, concrete stalls, etc. … under conditions similar to those met with in outside work” on the farm.

The drafting room was on the second floor directly above the concrete laboratory. A machine shop, lockers, and display room were above the forge, while wood work occupied the entire south wing above the power machinery laboratory and right-hand classroom on the main level.

Except for a blue printing and dark room, the third floor was entirely devoted to farm machinery. Here students had an opportunity to dissemble and reassemble a variety of farm machines.

The Dairy was a small building located to the south and west of the Engineering Building. This was where dairy husbandry – butter-making, cheese-making, and milk testing – was carried on.

West of the Dairy was the Stock Judging Pavilion, which was 150 by 52 feet and built of brick and stone with concrete floors. In the centre of this building was a large judging arena 66 by 24 feet to which “various classes of live stock” were brought in for judging work. This arena was surrounded by a gallery with seating accommodation for up to one hundred and fifty students. The Pavilion also included refrigerator rooms, a butcher’s department, emergency stables, and the veterinary science laboratory and office.

Near the Pavilion were the horse barn, beef cattle barn, dairy cattle barn, and swine barn. A sheep barn was still under construction when the school opened. During the summer, the college had added to its stock on hand through the purchase of a “team of general purpose horses of the best delivery wagon type” and several “Holstein and Shorthorn cows.” In October, Professor Peters and G. W. Wood went east to purchase additional livestock, chiefly dairy cattle and sheep.

Further west of these buildings was the Poultry Plant, a building 60X40 feet, constructed of solid brick and cut stone. It contained lecture rooms, incubator rooms, and egg rooms. Grouped around this building were the 30X60 ft. poultry fattening house, a brooder house, and three laying houses each 180 feet long.

The students’ residence and auditorium was by far the largest building on the campus. 550 feet long, with long wings running toward the rear, this three story building stretched along a bend of the Red River on the south side of the campus. It also had a basement and sub-basement and could accommodate “about 350 men and 200 women.”

The auditorium between the two residences could seat 1,500 people and was where meetings of the whole student body were held. It was also used for “farmers’ conventions, entertainments and final examinations.” The floors of all halls and lavatories were terrazzo and of the rooms fir. The rest of the woodwork was oak with a golden finish.

The residences provided every comfort. Each room was designed for two students and furnished with single beds, mattresses, blankets, comforters, and white spreads, study tables, chairs, bookshelves, and a dresser and washstand. Students had to supply “a pillow, two pillow covers, three sheets, four towels, and a laundry bag, all properly marked with the student’s name in full.” They were also required “to make their own beds, sweep and dust their rooms every morning, and keep them at all times neat and tidy.” The rooms were inspected daily at 8:30 a.m., and if unsatisfactory, the occupants could be asked “to room out.” Each room had two clothes closets that could be locked if desired, each of them large enough to accommodate a trunk no larger than “three feet long and two feet wide.”

The dining room was centrally located on the main floor and accessible from both the “boys’ and girls’ residences.” Adjoining the dining room was a large kitchen where the cooking for the whole institution was done. Equipped with ranges and a “refrigerator plant” and connected to an underground vegetable cellar, it was thoroughly up-to-date for the times.

The gymnasiums for the young men and young women of the college were located in the two wings to the rear of the residence. These were equipped with “high class apparatus including vaulting horses, parallel bars, special duplex pully weights, horizontal and vaulting bars, spring boards, horizontal ladders, climbing ropes, travelling rings, flying rings, stall bars, tumbling mats, medicine balls, basket ball outfit and indoor baseball.” Near the gymnasiums were the “shower baths, two swimming tanks, and lockers for gymnasium suits, bathing suits, and work suits.”

Sitting rooms and reading rooms were provided for the students, and there were quarters for the matrons, the dietician, staff members who desired to live at the college, and all the hired help.

One of the most important, but little noticed buildings on the campus was the central power house, which was located to the south of the Dairy building. It was equipped with four large boilers, each with a capacity of 600 horse power, which heated all the university buildings on campus. Power for the water works and college lighting was provided by the city. The entire facility was as up-to-date as it was possible to be in 1913.

The new college was formally opened on February 12, 1914, by the Hon. Sir Rodmond Roblin, Premier of Manitoba, before an assembly of approximately 2,000 visitors and students at the residence auditorium. Visitors had been arriving all day by streetcar for tours of the buildings by the senior students, and many had remained for the official opening at 8:00 p.m. In addition to the premier, about thirty of the leading men of the province were present on the platform, and a number of them spoke, including President Black, head of the Manitoba Agricultural College, the Honourable George Lawrence, Minister of Agriculture, and Major H. M. Dyer, Chairman of the Board of Directors. One of the highlights was the unveiling of a full size portrait of Premier Roblin, which plainly touched the premier, who gladly agreed that it be hung in the halls of M.A.C. He then gave an “instructive address” and declared the college open “amidst thunderous applause.” In the words of the Gazette, this brought to a close an event that would be remembered “as marking a gigantic stride in developing scientific agriculture in Manitoba.”

Source material

“All buildings where teaching done finished in oak with terrazzo floors in halls and laboratories and elsewhere the finest edge grained fir.”

The New College. P. 13.

the President’s residence.”

Students had visited the college in March 1913.

Pembina highway had been paved from the city limits past the college farm and a gravel road built through the centre of the farm to the boulevard in front of the administration building.

)

Two new departments had been added in the Graduate courses, in the past year, namely Horticulture and Forestry. The ones already in place were Animal and Field Husbandry, Dairying and Agricultural Engineering. The reason for the additions was that it would give young men “an opportunity to secure a training in the theory and practice of Prairie Horticulture and Prairie Forestry, that they would be in a position to direct work of this kind in our prairie provinces.” Trained horticulturists were needed at the experimental farms, the Forestry Brance needed inspectors and assistants at the forestry farms; the railroads for men to direct the work of station ground improvements, and to assist in the horticultural work which those larger lines are undertaking; and the cities and towns for men to assist in the work of civic improvement. They were trying to combine theoretical and practical aspects. In botany, they would make a study of the botany of our cultivated plants, which emphasis will be place on such phases of botanical work as Plant Pathology, Plant Physiology and Plant Histology. Entomology as it applies to the treatment of insects affecting horticultural plans and forest trees, will receive careful consideration. In chemistry, attention paid to the chemistry of insecticides and fungicides, while in Physics the subject of soil drainage would be an emphasis. “In he splendid new Horticultural and Biology building at St. Vital, provision ahs been made for giving thorough instruction in the various branches of horticultural and biological work. The building was well arranged and commodious, attached to the building were a range of greenhouses, where studies could be made in plant growth and greenhouse methods. Outside work also. Ten acres of well drained, loamy soil, well adapted for horticultural work, to make practical studies of hardy fruits and ornamental plants, and where training could be given in horticultural practice such as budding, grafting and general care of nursery stock. (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Oct 1913, p. 18-19)

Demonstration Work in Drainage. A portion of the college farm had been drained by prison labor under the direction of the Department of Soils. This is used to demonstrate the value of using tiled drainage in Manitoba. They experimented with different depths of tiles and found tht those placesd at 2 1 ½ to 3 feet below the surface were not damaged by traction engines driving over or cultivating them . (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Oct, 1913, p. 20-23)

Animal Husbandry Notes. All the buildings were complete and the college livestock was housed in the barns by Oct. 28. The sheep barn was the only one not completed. “The judging pavilion, a brick building 156 feet long and 52 feet wide will be ready for use by the time college opoens. This buioding contains three large lecture and judging rooms. The main live stock judging area occies the central portion of the building. The judging arena is 66 feet long copy this article (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Oct 1913, p. 29)

The Diploma Course was now three years instead of two. It was practical and nature and not preparatory for entry into the BSA program. It was designed to give practical training in the shortest possible time to men who desired to return to the farm. (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Oct 1913, p. 32)

Home Economics. Copy (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Oct 1913, p.41)

Extension Section. Copy this (University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, Nov 1913, p. 90

The following description of the college facilities has been heavily influenced by general information provided in the October 1913 issue of the M.A.C. Gazette. See University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1, (Oct. 1913) p. 13-17.

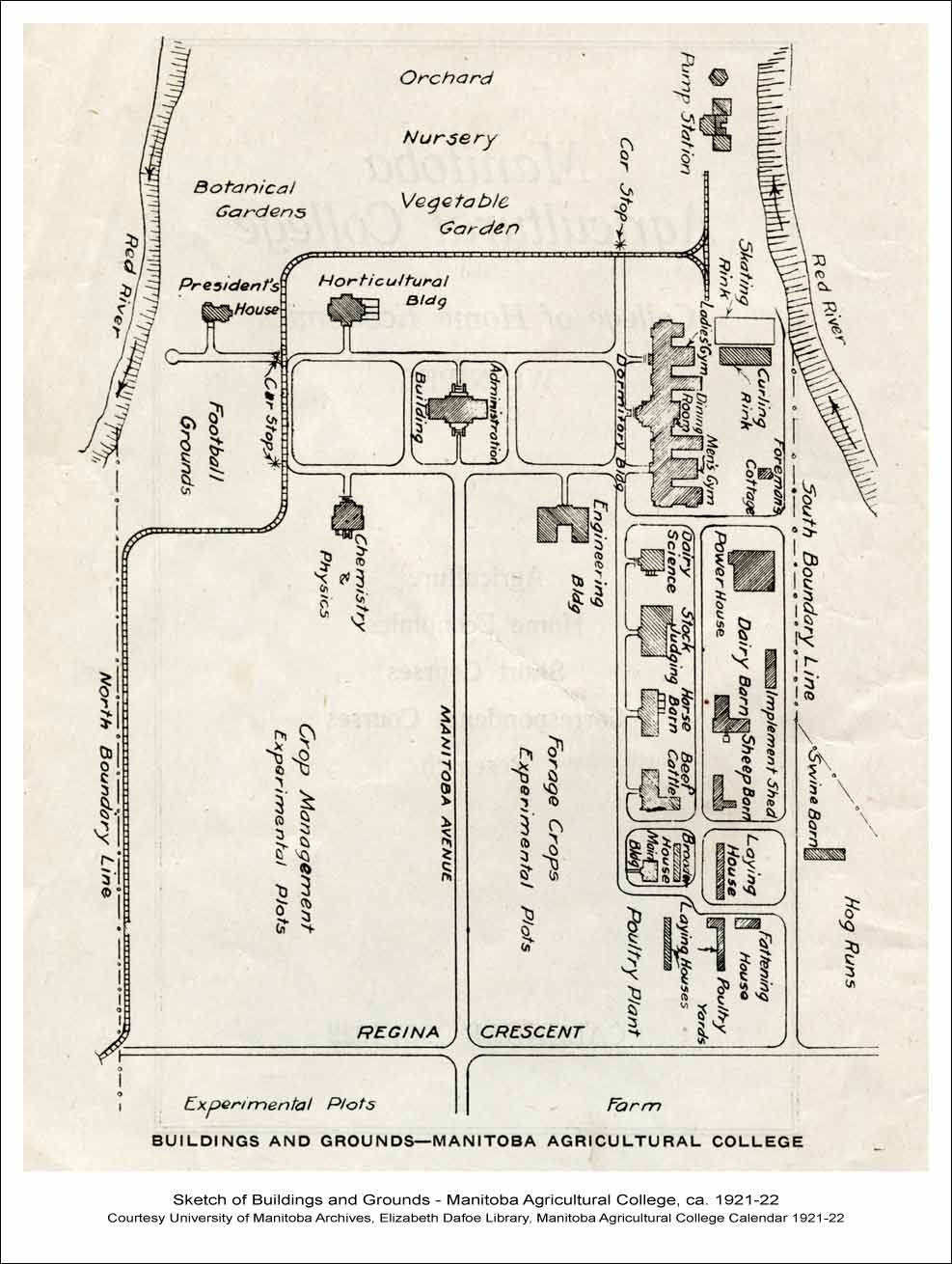

A regular street car service to and from the City of Winnipeg started in October 1913.The line entered from Pembina Highway along the north side of the campus in an easterly direction, made a ninety degree turn to the right (south) toward the Chemistry & Physics Building, then turned again at ninety degrees to the left before reaching that building. Moving eastward just beyond the President’s residence on the left and the Horticultural Building on the right, the line turned again ninety degrees to the right (south) and terminated at a spot between the student dormitories on the right and the pumping station on the left.

They were a select group. Students in Agriculture had to be at least sixteen years of age, of sound moral character, and free from “tuberculosis and other contagious diseases.” They needed also to have spent “at least two summers in practical work on a farm,” and possess sufficient “English education” to be able to “profit by attendance at lectures.” University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Manitoba Agricultural College Calendar (1913-1914), 16.

The M.A.C. Gazette, v. 1, no. 8 (Feb. 1912), 1.

Three million dollars was a great deal of money, considering that the average wage for a labourer in 1913 was $1.00 a day.

The average cost for books was $10.00 a year. University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Manitoba Agricultural College Calendar (1913-1914), 18.

Although it was the main floor, the office numbers, such as 209, Bursar’s Office, 210, Registrar’s office, indicated that it was the second level of the building.

The annual tuition fees for Manitoba residents were $10.00 (3-yr diploma) and $20 (5-yr degree). For non-residents, the fees were $30 (2-yr diploma) and $40 (5-yr degree). Additional charges included: laboratory fees, $3.50; sick benefit, $2.00; medical examination, $1.00; and a caution fee of $5.00 (returned if no damage done). Students in their fifth year had to pay $10.00 for their degree. Students also paid $1.00 for a “white suit for dairy” and $2.00 for a “suit for workshop.” Smokers had to pay a compulsory $3.00 fee that entitled them to use the smoking room. If students failed to pass courses during the year, they had to pay fees ($1.00 each for diploma and $2.50 each for degree) to write supplemental examinations. An extra fee of $5.00 was also charged for late registration, non-refundable except for those leaving the college because of illness. University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Manitoba Agricultural College Calendar (1913-1914), 16.

Otherwise, students would have been required to miss classes in order to travel by street car into Winnipeg and visit a bank. At that time, banking hours were much more restricted than they are now.

Prof. G. A. Sproule, B.A., was the head of the English Department, and he also taught Book-Keeping. C. R. Hopper, B.A., lecturer, was his assistant.

The Professor of Animal Husbandry in 1913-1914 was W. H. Peters, B.S.A., assisted by two lecturers, F. W. Crawford, B.S.A. (1911), and G. W. Wood, B.S.A.. Lieut. Walter Crawford, Military Medal, was a graduate of the college. He joined the 4th University Company in September 1915, transferred to the P.P.C.L.I., and served in France and Belgium, before returning to Canada.

The museum was later moved to the ground floor of the Horticulture and Biology Building. After he arrived in France, Frank Whiting remembered the college museum. Whether his macabre sense of humour was natural or acquired by the exigencies of the battlefield, Frank devised a cunning plot to add “Alphonse” to the museum’s collection. “Alphonse,” or rather the skull of this unfortunate herbivore, either bovine or equine, we do not know, possessed a prominent bullet hole in his head, proof positive of a cruel and unfeeling enemy and guaranteed to raise the patriotic ire of outraged young agriculture students! With the help of a willing censor, Frank smuggled Alphonse out of France, and an eager Alex MacWilliam made sure that it was displayed prominently in M.A.C.’s little museum.

The head of Field Husbandry was Prof. L. A. Moorhouse, M.S. His assistants were Prof. T. J. Harrison, B.S.A. and J. H. Bridge, B.S.A. (1913), demonstrator.

The lecturer in English was C. R. Hopper, B.A. He also taught History and Agricultural Economics. Lieut. Clark H. Hopper, M.M., enlisted in May 1916 with the 196th University Bn. and served with the 11th Brigade, Machine Gun Section. After the war, he returned to the university faculty.

Prof. F. W. Broderick, B.S.A., was the head of the Department of Horticulture and Forestry.

Prof. V. W. Jackson, B.S. (Honours), was the head of the new botany department.

Prof. Lee was head of the Department of Bacteriology.

Prof. G. W. Morden, M.A., Ph.D., Doct.-Ing., was head of the Chemistry Department. R. A. Cunningham, B.Sc. was lecturer. Lieut. R. A. Cunningham enlisted with the 196th University Bn. in February 1916, transferred to the 46th Bn, and served in France, where he was killed 27 September 1918, just weeks before the end of the war.

Professor F. G. Churchill, B.S.A., was the head of the Physics Department.

According the Gazette, the classrooms in the new Dept. of Chemistry were large and equipped with soapstone-topped working tables of the latest design. There were “five laboratories for analytical and experimental purposes, an Electro-Chemical laboratory, a balance room and acid digestion and sulphuretted hydrogen chambers, the last mentioned two having white tiled walls.” The fume cabinets had the most up-to-date “steam heated baths,” and the laboratories for the advanced students also had “electrical appliances for heating and drying.” Distilled water for each laboratory was piped from a “steam operated still in the attic.” See University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1913-1914, v. VII, No. 1 (Oct. 1913), 19.

Professor L. J. Smith, B.S., was the head of the Department of Agricultural Engineering. W. J. Gilmore, B.S.A.E., was Assistant Professor, and Robert “Bob” Milne, B.S.A., Lecturer in Agricultural Engineering.

There was also a large attic for storage and a basement underneath the central section of the building between the two wings. See MAC Gazette, v. VII, no. 6 (Mar. 1914), 412.

Not all this equipment was in place in March 1914, but that was the plan. See MAC Gazette, v. VII, no. 6 (Mar. 1914), 413.

R. Watt was the Instructor in Blacksmithing.

The shop was “equipped with an emery grinder, two lathes, a large power drill, and a shaper” with the hope that “a milling machine” would be added “at an early date.” See MAC Gazette, v. VII, no. 6 (Mar. 1914), 413.

D. L. Cormack was the Instructor in Carpentry. His shop was equipped with “twelve foot benches, each for four students, and ample power and hand wood working tools.” See MAC Gazette, v. VII, no. 6 (Mar. 1914), 413-414.

Prof. J. W. Mitchell, B.A., was in charge of Dairy Husbandry. W. J. Crowe, Instructor in Butter Making, had just been appointed provincial instructor in dairying, so his position had not been filled when classes started in the fall of 1913. E. H. Farrell was the instructor in Milk Testing, and I. Villeneuve, the Instructor in Cheese Making.

Cattle judging was an important part of the degree programme in agriculture. Each year a team of students from the fourth and fifth year was chosen to attend the stock judging contest at the International Live Stock Show in Chicago. Since that contest was held on November 29 in 1913, there was little time to prepare. Consequently, students wishing to participate were encouraged to be present at the first class in judging after school opened October 28 when the first competitive practice was to be held. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29-30.

Here students learned about the slaughter of animals and the cutting and curing of meats. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

The laboratory was set up for lectures, clinics, and stock judging as well. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

The horse barn was brick veneer over a wooden frame, 136 feet long and 40 feet wide, with a hip roof and interior “finished with cast iron posts and open work iron stall partitions.” It could accommodate forty horses. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

Similar in construction to the horse barn, the beef or feed cattle barn was equipped with “tubular steel stalls and litter and feed carriers.” A brick silo and root cellar were attached to it. The building could house seventy to eighty head of cattle. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

The dairy barn was of wood construction with a shingle finish. It had a stone silo, root cellar, and milk room attached to it and could accommodate 32 cows and an equal number of young cattle. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

This building was 120 by 30 feet and could accommodate 120 hogs. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

G. W. Wood, B.S.A. was a newly appointed lecturer in the Animal Husbandry Department. Raised on a mixed farm near Lachute, Quebec, that specialized in dairying and particularly in pure bred Ayrshire cattle, Mr. Wood was experienced in the development of pure bred dairy stock and was also a prize-winning stock judge. His role was to develop “the Dairy side of the Animal Husbandry Department.” M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 35.

M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 29.

Prof. M.C. Herner, B.S.A. was the head of Poultry Husbandry.

Board was $3.25 a week and the room rent $1.00 a week. Room rent had to be paid each term in advance - $8.00 on October 28 and $13.00 on January 2. Board was paid monthly – Oct. 28, $13.00; Nov. 25, $13.00; Jan 2, $13.00; Jan 30, $13.00; Feb. 27, $16.25. Payment had to be made promptly on the assigned days, or the weekly fee went up to $3.50. University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Manitoba Agricultural College Calendar (1913-1914), 15-16.

The annual cost of laundry for one’s personal effect was about $10.00. University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Manitoba Agricultural College Calendar (1913-1914), 17 and 18.

Most ate in the dining room, as there was an extra 10 cents per meal charged for those wanting their meals in their rooms.

In the past, Miss Spackman had “heroically undertaken all the varied duties of matron, housekeeper, dietician and frequently nurse for the while residence, girls and boys.” However, when the new residence opened in the fall of 1913, she was only in charge of the boys’ residence. Miss Turpin had been appointed matron of the girls’ residence. M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 33-34.

In the fall of 1913, Miss Rutherford was appointed dietician,” having charge of all pertaining to dining room and kitchens.” M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 1 (Oct. 1913), 34.

The M.A.C. Gazette, v. VII, no. 6 (Mar. 1914), 425.

Return to Top

Last updated:

July 16, 2010

This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada License. |

![]()