SSNS Home > Senior Years > Curricula 9 to 12 > Grade 11 > Canadian History > Remembrance Day > Whiting > Delvoie Family

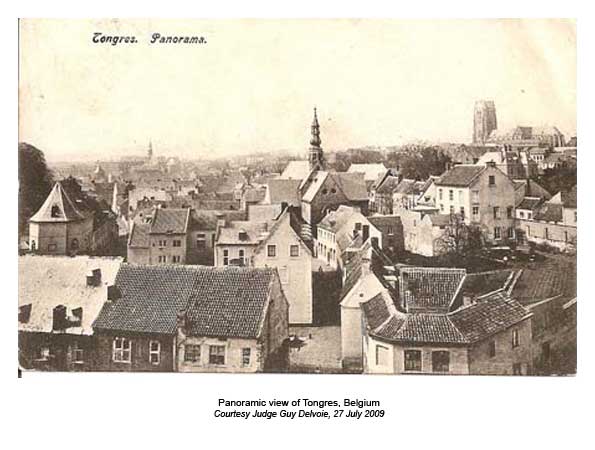

In April 2009, Raymond Shirritt-Beaumont began the search for the Delvoie family that sheltered Frank Whiting at the end of the war. Surfing the internet, he discovered Guy Delvoie, a judge of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, which is centred in Brussels. He immediately contacted Judge Delvoie on the hunch that he might be connected to the Delvoie family of Tongeren/Tongres. Within a day, he received a reply that began an exciting exchange of information over the next few months.

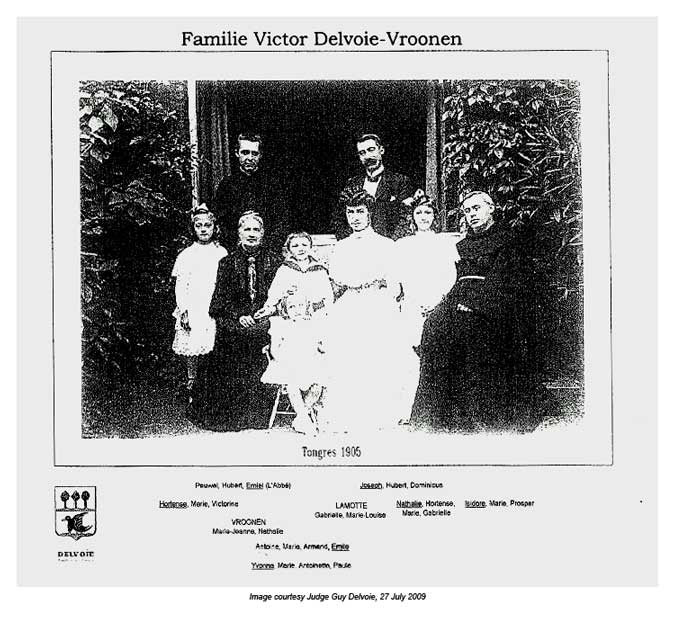

Guy was indeed a relative of Émile and Hortense Delvoie. Their common ancestor was named Lambert Joseph Delvoie, a wine trader, who died at Tongeren/Tongres on 5 July 1855. He had two sons, the elder named Victor Rochus Delvoie (1833-1904), grandfather to Hortense and Émile, and the younger named Antoine Julien Delvoie (1837-1904), great-grandfather of Judge Guy Delvoie. Antoine was a “notaire,” who functioned much like a lawyer or town clerk and was licensed to prepare legal documents. He lived at Canne or Kanne, which was located about eighteen km east of Tongeren/Tongres near the Dutch border.

Victor Delvoie, the grandfather of Émile and Hortense, was a physician, who held several public offices and was prominent in the Catholic Workers’ Movement. He was married twice, first to Marie Elisabeth Constantia Arckens, by whom he had twins, Pieter Lodewijk Paul Delvoie and Marie Constance Emma Delvoie. Their mother died in 1861, a week after her children were born.

Victor’s second wife was Marie-Jeanne Nathalie Vroonen, by whom he had six sons. Joseph Hubert Dominique Delvoie, father to Émile and Hortense, and his twin brother Armand Jules Marie Delvoie were born 26 May 1868. Armand died at eight years of age in 1876 and two younger infant brothers died in 1874 and 1878. Isidore Marie Prosper and Paul Hubert Emile, the two remaining brothers both became Roman Catholic priests.

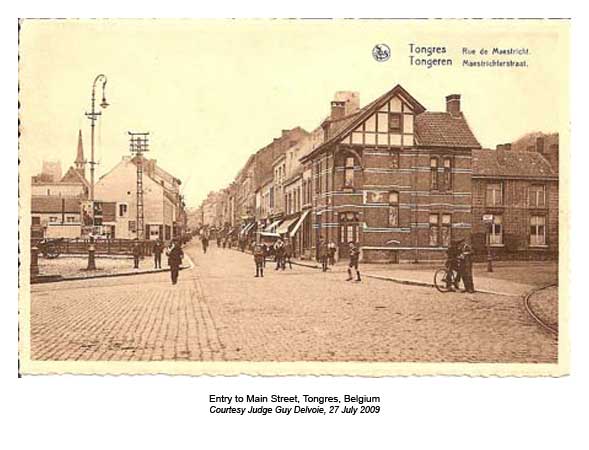

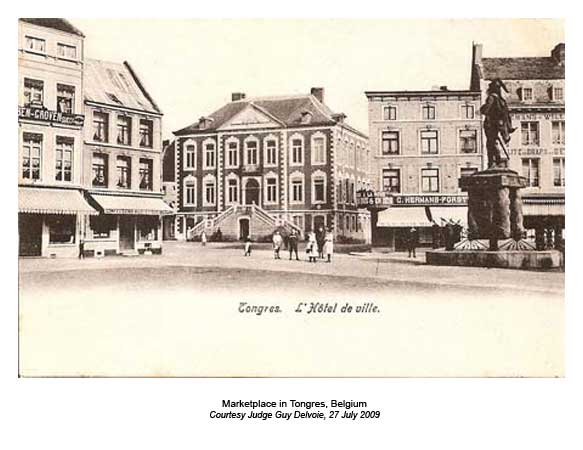

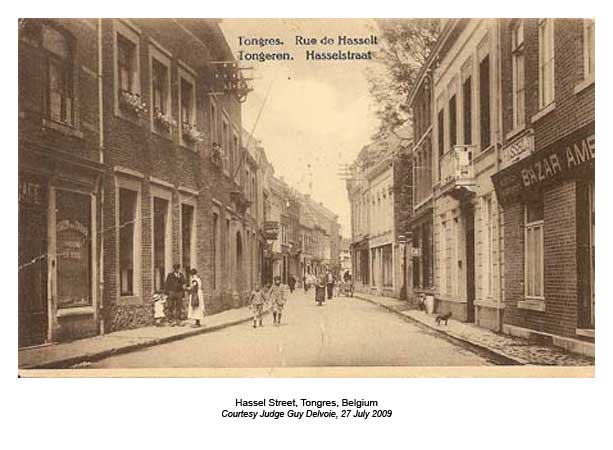

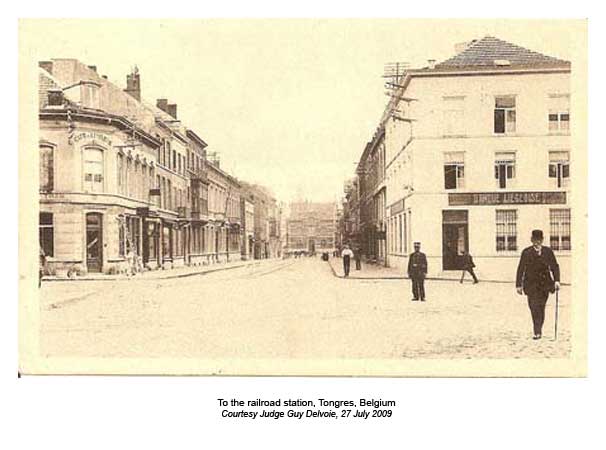

Joseph Delvoie (1868-1921) was Émile and Hortense's father, and it was his house in Tongeren/Tongres that sheltered Frank Whiting in late 1918. Joseph was a lawyer, who, like his father Victor, held several public offices, including councillor in the Council of the province, and deputy-senator.

Joseph was married in 1897 to Gabrielle Marie-Louise Lamotte, who was from the little village of Navaugle, located 88 km south of Tongeren/Tongres near Rochefort in the French-speaking section of Belgium. She lived with her parents in the Château de Navaugle, which gives some idea of her family background and status.

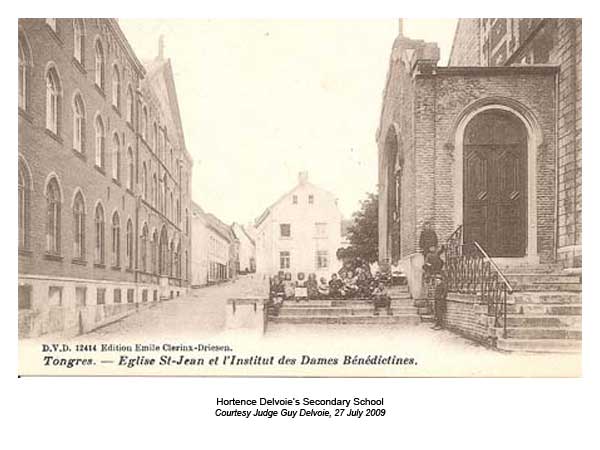

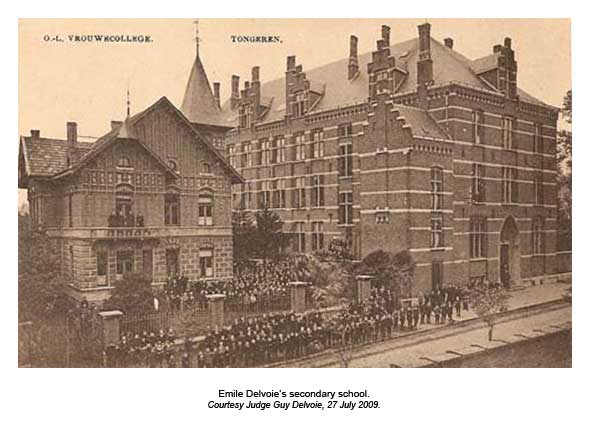

Joseph Delvoie and Gabrielle Lamotte had four children. Hortense Marie Victorine Delvoie was their second child, born 5 November 1900. Antoine Marie Armand Émile Delvoie, their third child and only boy was born 9 September 1902. There were two other daughters, Nathalie Hortense Marie Gabrielle and Yvonne Marie Antoinette Paule, neither of whom married.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joseph Delvoie died at Tongeren/Tongres, 25 July 1921. In 1924, his wife Gabrielle Lamotte moved with Nathalie, Émile, and Yvonne to the Chateau de Tellin in a village of the same name near the town of Rochefort, the area where she was born. Gabrielle died at Tellin, 10 April 1961.

Hortense Delvoie had married by the time her mother moved to Tellin. Her husband was Charles Nicolas Eugène Nagant, who was authorised by Royal decree in 1957 to change his name to Nagant de Deuxchaisnes. She and Charles had three sons, one of whom, Charles Jr., became a physician and professor at the Université Catholique of Louvain. Charles Jr.'s son, Didier Nagant de Deuxchaisnes, is a Belgian diplomat.

|

|

Émile Delvoie became a mining engineer and director of a radio factory in Tongeren. In 1926, he married Maria Josepha Antonia van Donant. They had four children, two daughters and two sons, one of whom, Paul-Émile Delvoie, was also a mining engineer like his father. Interestingly, Frank Whiting’s eldest son Frank was also a mining engineer and geologist.

This brief genealogy of the Delvoie Family illustrates how a little research can produce a wealth of information on human connections, however brief, across generations and time. It should encourage those who are researching soldiers of World War I to follow all leads, even the most obscure, because they may open up gold mines of heretofore unknown and unexpected history.