SSNS Home > Senior Years > Curricula 9 to 12 > Grade 11 > Canadian History > Remembrance Day > University Co. Soldiers > Whiting

Whiting, Frances James “Frank”, enlisted in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, originally of London, England. Occupation: Farmer. Military service: Reg. No. McGill 113, 2nd University Co., PPCLI, Attestation Papers.

Additional Biographical Information:

1915-1919

“Whiting Francis James McGill 113. Born in London, England Mar 1892. Employed as a farmer before enlisting in the 2nd University Company 25 May 1915. Arrived in England and posted to 11th Bn. 18 Jul 1915. Crossed to France 24 Aug 1915. Joined the PPCLI in the Armentieres Sector 1 Sep 1915. Granted 9 days leave from 27 Mar 1916. General Action: Battle of Mount Sorrel. General Action: Battle of Flers-Courcelette. General Action: Battle of Ancre Heights. Hospitalised lacerated mouth 16 Nov 1916. Discharged 6 Dec 1916. General Action: 1st Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele). General Action: Battle of Amiens. General Action: Battle of Scarpe. Reported mission in action 27 Aug 1918. He was bombing down Friction Trench when the party was heavily counter attacked and had to retire. He was seen to be hit and fall in the trench. The next morning when the trench was retaken his body was not found although there were three other men who had been with him lying dead in the trench. Captured during the Battle of the Scarpe 27 August 1918. Repatriated 9 Dec 1918.” See Stephen K. Newman, With the Patricia’s in Flanders 1914-1918 (Saanichton, British Columbia: Bellewaerde House Publishing, 2000), 187.

Compare for accuracy with Frank’s Diary. For instance, on 16 Nov 1916, Frank wrote, “On the way back [A. H. H.] Good, myself and another fellow was caught between an advancing lorry and the side of the trench and I was scraped on the knee and right thigh. Walked down to Bath dressing station and got tied up. Sent down to 9th field aid station a mile down the trench. Stayed there overnight.”

1915

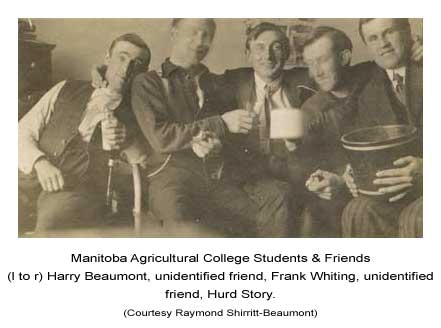

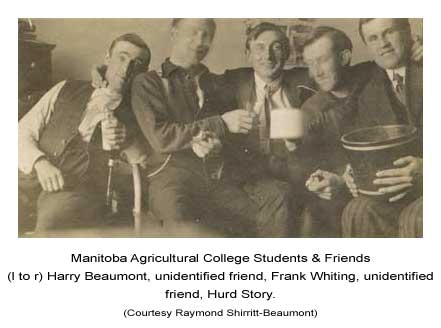

Frank sent a letter dated 7 October 1915 to Miss Wood, the Manitoba Agricultural College [M.A.C.] librarian. It was subsequently published in the M.A.C. Gazette, with an accompanying photograph of F. J. Whiting (’18) in uniform, McGill 113, 5 Platoon, 2 Company P.P.C.L.I. It reads as follows:

France, Oct 7, 1915. You will be surprised to hear I am in the trenches as I write this. Have been more or less at the front since writing you at Rouen. I think our company broke the record for rapid training. Quite a number joined after I did, and I made it in less than a hundred days from the farm to the trenches.

This is really a very easy spot where we are stationed now. A few bullets come whizzing around once in a while during the night, but in the day time all is quiet unless they start shelling. They sent half a dozen or so big ones yesterday morning, but no one was hurt. These were the only shells received since we have been here – getting on for a week. We heard a heavy bombardment up La Bassee way before yesterday, and rumor has it that we suffered a reverse. You people over in Canada know more about how things are going on than we do in the actual firing line. That is, the big movements, of course.

There are lots of little things going on all the time right in our little part of the trench that are quite interesting enough from our point of view. The civilized man cannot imagine the multitude of minor annoyances that the soldier has to put up with, such as sleeping with all clothes on, including equipment, for weeks on end, guard duty day and night all the time, sleep being obtained by curling up alongside the man who relieves you, right in the mud very often. We get the afternoon off – my shift, at least – during which time we cook and eat dinner, sleep for a couple of hours, cook and eat supper, and go on guard again at five o’clock. After the first three or four days you don’t mind it, having by that time got into the knack of being able to sleep standing up, if possible.

Now I must cut this short, as my notepaper is running out and goodness only knows when I can get more. Give my regards to all my friends at the College. Frank J. Whiting.

University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, The M.A.C. Gazette, 1914-1915, v. IX, No. 1 (November 1915) 20-21.

1918

Editor, Managra.

Dear Sir: I figure on being back in Canada about the end of February and I will certainly pay a visit to the old coll. On my way home.

As to news, I have seen Fuzzy Houghton and Mitchell ’18. They are both well and were having a great time in Mons when I passed through. They told me Andy Robertson (’18) had been killed. Jenkins (’17) is reported missing, believed killed.

Sincerely,

Frank J. Whiting,

P.P.C.L.I

(University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Managra, 1914-1915, v. XII, No. 1 (January 1919) 13.

1918

Letter from Pte. F. J. Whiting

Repatriation Centre

Valenciennes, France,

December 4th, 1918.

M.A.C. Red Cross Society.

Dear Friends:

I am in receipt of a packet of chocolate sent to me through your from the College for which please receive my most sincere thanks, as I received it at a most opportune moment; also under circumstances perhaps a little remarkable when one considers the facts of the case. As they may interest a few of my old friends who may be still at the M.A.C. I will give a short resumee [sic] of my actions for the three months preceding my receipt of their parcel.

I thought at first of writing of my adventures to the “Managra” and putting them in story form, but after reflecting upon the number of similar cases that will no doubt be given publicity now the war is over, I decided, like wiser men, to “wait and see.” Meanwhile here are the bare facts.

On the 27th August I had the ill luck to be taken prisoner alive and well and all alone. The fault was none of mine, but nevertheless it looked bad. Not caring for the company I was compelled to keep I escaped two weeks later and made my way almost to our lines. One German outpost was between me and our boys when I was retaken and sent back.

Two weeks later I tried again but had even worse luck and was being sent to Germany under an escort of three men when I made my third and last attempt. This time I was successful and got clear away from the Germans. Some Belgians found me and clothed and fed me and kept me hidden until the armistice was signed. I then put on my khaki and started out on foot to make my way to the coast. After a number of small adventures I fell in with a party of British who had also been prisoners. They were being sent to Brussels by the Belgian authorities. We arrived in Brussels that night about 10 o’clock, and while being taken to a rest home for the night I met three old friends from my old regiment. They were just on the point of starting out for Mons – 60 kilometres away – by motor, and without any ceremony hauled me in along with them. About two o’clock that night we reached Mons where the regiment was stationed. The next day I did nothing but shake hands and answer questions to everybody from the Colonel to the platoon cook. And to cap a series of lucky coincidences the mail corporal informed me he had a parcel in the post office for me that had just come in.

Well, that is about all. Since then I have donned a new suit of khaki and am on the way to England where I expect a month’s leave before going to dear old Canada.

With best regards to all,

I remain, Sincerely,

Frank J. Whiting.

University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Managra, 1914-1915, v. XII, No. 2 (February 1919), 13.

1919

Whiting-Irving

After dodging German shells for more than three years as a member of the famous P.P.C.L.I., it was officially announced that another boy of the ’18 class has been struck through the heart by one of Cupid’s searching darts. Frank J. Whiting, of Wolfe, Sask. And Jean Beaumont Irving were united in marriage at St. Mary’s Church, Ambleside, Westmoreland, England, on January 27th, 1919. It is expected that the young couple will leave for Canada soon and we hope to have the pleasure of meeting them on their way to Wolfe, Sask., where they will reside. The Managra extends its congratulations and good wishes.

University of Manitoba, Archives and Special Collections, Managra, v. XII, no. 2 (February 1919), 47.

1926

The following article, which is a summary of Frank’s visit to France and Belgium in 1926, appeared in The Grain Growers’ Guide, June 15, 1926, 4-5. It is a testament to the speed with which reconstruction occurred in both countries after the war. In many places Frank found the countryside so changed that it was difficult for him to locate the once familiar landmarks.

Old Battlefields Revisited

F. J. Whiting, ex-Princess Pat, writes a letter to an old comrade.

Dear Buddy:

I promised to set down in writing for you my impressions upon re-visiting the old battlefields last winter, after an absence of eight years.

My first feeling was one of amazement. It is nothing less than astounding that in the few short years since the armistice, villages, towns, cathedrals, roads and farms have in nearly all cases been restored or rebuilt.

When my wife and I arrived in Ypres one evening last February, it took me at least half-an-hour to find my way to the Cloth Hall, and there get my bearings. Opposite the station one sees a complete row of quite good hotels and cafes. On the left stands another row of thirteenth-century Flemish buildings that looks as if it has always been there. The houses have been built on the same old sites, following the same narrow winding streets. As nearly as possible even the same style of buildings have been erected Even the milk carts are still hauled by a dog or two either in front or underneath.

In Ypres the smell of wet rubble and plaster that we used to know has given place to that of all French and Belgian towns – stale beer and vegetable soup! The churches and cathedrals have either been rebuilt or are in process of reconstruction. The Cloth Hall tower has been shored up with scaffolding to make it safe, but that is all that has been done there. There is some talk of leaving it as a memorial, but the popular opinion has it that it will be rebuilt when the money can be raised.

One of the first spots I revisited in Ypres was the eastern ramparts. Here I tried to locate the old dug-outs, but failed. They are all either filled in or caved in. All along between the Lille and Menin gates are backyards, chicken runs, ash dumps, heaps of rubble. The Menin Gate is the scene of great activity. They are erecting an arch over it, surmounted by a lion in repose. On the base of the column will be inscribed the names of 60,000 British and Dominion soldiers who fell in the salient but have no known graves.

From the Menin Road we struck across towards Passchendaele. Along here one sees dozens of pill-boxes. Those that happened to be in people’s back-yards are being utilized as dog-kennels, piggeries or chicken-houses. Those further out in the fields are being plowed around, rained upon, and as far as possible, ignored. A few have been blown up and removed, but it is a costly business – those Germans knew a lot about reinforced concrete!

At Spree Farm we lunched with the present inhabitants. They told us they could not return until 1921, as the land was in such condition that it was impossible to plow or work in any way. It needed at least three years to settle and drain. Even yet odd fields may be seen where the shell holes still lay, half filled with water, the bull-rushes telling of destroyed natural drainage even on quite high land. This farmer’s back-yard contained several tons of rusty and very muddy war souvenirs, awaiting the periodical visit of the junk man who paid around 30 centimes a hundred kilos for old iron and baled wire, and up to four francs a kilo for brass, copper and lead.

Grafenstaefel has vanished, though I saw where the Willow Road, a few yards to the left, had been repaired with planks and logs.

Hell-fire corner on the Menin Road is only recognized by the large notice board that informs all who pass of its once grim association. Another board points south to China Wall British Cemetery. Thither we wandered and though we had the help of the gardener in charge, I found it impossible to get my bearings. Not a trace of the sand-bagged wall remains. On all sides are fields of fall wheat, bordered by ditches, farm houses and barns smelly with top-dressing.

From Outpost Farm on the Menin Road, across through Sanctuary Wood to Hill 62, the Canadian government is building a splendid road. Maples have been planted on each side and it is appropriately named Maple Avenue.

At Outpost Farm there was an Imperial War Graves Commission lorry loaded with coffins of men recently discovered and on their way to being re-interred in the nearest cemetery. I learned that an average of 35 bodies per week are still being found in the Ypres section alone, and in spite of the fact that the old composition identification discs have proved worthless, 60 per cent of the bodies found are identifiable. One man had just been discovered, and the only clue to be found on him was the corner of a money order receipt. From this the commission has good hopes of being able to trace his identity.

Most of the bodies found are discovered by the peasants, who, in their search for brass and copper fragments, dig over the battlefield from a depth of a foot to five feet. As soon as the digger is sure that the corpse he has found is dressed in Khaki, he must cease digging and phone the Graves Commission immediately. At once a party is sent out, and every possible care is taken that no chance clue may be overlooked that could lead to his ultimate identity. The peasant is awarded 10 francs for every body he finds, providing same has not been unduly meddled with.

A Canadian cemetery is situated on the hillside that overlooked the Canadian trenches by Sanctuary Wood during 1916. Only a trace of the wood now remains. Zouave Wood and Maple Copse are only patches of scrub. Not a single tree remains. I searched in vain for the “Bird-cage” where Fritz kept deadly watch for sign of movement down in the hollow. Several pill-boxes are still to be seen on the ridge, but none that I could be sure was our old friend of 1916.

Passing along the north side of Maple Copse we came to a drainage ditch running south, and there, lo and behold, a bath-mat! Sure enough the old communication trench from Zillebeke to Sanctuary Wood. The bath-mat, or duck-board, as some called them, crossed the ditch about two feet down. And right by it six inches of the barrel of a Lee-Enfield rifle stuck out! It runs in my mind that we used to call that trench “Lover’s Walk,” but I may be mistaken. During the spring of 1916, nightingales used to sing in the woods by the side of that trench when there were not too many shells dropping near. The sweet notes would echo and re-echo up and down the hillsides and the air was fragrant with wet, earthy smells and young leaves. Oh well, the second of June changed all that. I hope the nightingales made a successful retirement!

Hill 60 still looks very much the same as it did at the close of the war, although tons and tons of material have been salvaged from it there still remains plenty to be done. Unexploded duds of all kinds and sizes from peaceful-looking aerial torpedoes to murderous little Mills bombs and pineapples; potato mashers, plum puddings, nine-two’s, Stokes mortars, rifle grenades, their drive shafts rusty and bent; tin hats, rifles of several makes and parts of rifles, wiring irons, pieces of sheet iron, parts of equipments and uniform; and, if one looks carefully, bones and fragments of bone are on that hill of death.

Three or four Belgians were digging for brass nosecaps. These posed for a photograph, but the day was too dark and the picture spoilt. Verbrandt Mill, as can be seen in the Hill 60 picture has been rebuilt.

Returning to Ypres we skirted the south side of Zillebeke Lake. The communication trench that once zigzagged by it has been filled in and not a trace remains. The Bund dugouts have also vanished. Two ragged depressions in the side of the road that now runs along the dam are the only signs that speak of the khaki-clad hive of humanity that once sheltered there. Those huge chambers and caverns are caving in. The duck board promenade outside the entrances has been utilized for fuel no doubt; at any rate it has gone, and rank grass and dead weeds now wave dismally where once the brass-hat and the red-tab flourished while muddy privates glanced furtively to see if their buttons were very badly tarnished. The railway dug-outs are in the same condition- even the little lake hard by has been partly drained. There used to be very good fishing there in that lake if one carried a few Mills bombs along with his other tackle.

From Ypres we took the steam-train south to Kemmel. I had intended dropping off at Voormezele as I had heard that a lot of the men of my old regiment, the P.P.C.L.I, were buried there. However, so changed was everything and so lost was I that we passed right through the village without my realizing it.

We went one night in Kemmel, staying at the café La Grande Polka on Suicide Corner. The chateau has disappeared. It was burned down in the latter part of the war and now only the vaults remain. The owner has rebuilt under Trout Kemmel, facing the east.

The Kemmel huts have also gone the way of nearly all our once pleasant abodes. Here, once upon a time, we were thrice assembled to listen to the sergeant-major who droned out a horribly protracted list of poor wretches who had been absent without leave while their regiment was in the trenches. The date they were missed, the date they were captured and the date they were tried and sentenced, and finally the date “the sentence was duly carried out!” Truly a cheerful entertainment and one doubtless calculated to stiffen the morale of the troops.

We paid a visit to old Mother Taccoen, who, with her two daughters, sold chips and coffee from the old post office in Kemmel. For two-and-a-half years within a mile of the front line; always within hand-breadth of sudden death and disaster; always with the roar of guns in her ears, and never an hour, day or night when soldiers could not enter her basement café.

The dear old soul was delighted to see us and regaled us for hours with tales of the war. She was within two miles of the Messines show. Participated in the buried treasure hunt in [page 5] Wulverghem trenches; was nearly bayoneted by a Royal Scot; a wag who, when she ran out of pepper gave her a tin of Keatings! (Ed. Note. – Keatings is a brand of insect powder, popular in England); a tale of two captains, one of whom married one of her daughters and the other who, when he revisited Kemmel, three years after, dropped dead; what she did with 1800 pounds of sugar when the Germans were advancing in the spring of 1918. One could write a book on that old lady’s tale of the war. And colourful! I’ll announce it, Buddy!

The old trench line that once ran in front of Neuve Eglise, Wulverghem and Kemmel, has been almost completely erased. In fact, if it were not that the map proved the line passed through there we would never have guessed it. Villages, farms, quiet lanes and pasture fields, where once was the most complete desolation.

Armentieres presented a very busy scene when we passed through. Most of what was totally destroyed has been rebuilt. Those buildings that could be restored now hardly show a trace of war. The same is true of Lens and Lievin. One point I noticed was that although the roads are in a good state of repair there are no sidewalks yet. Everyone seems very busy and fairly prosperous. The mines have been restored, and most of the factories are once more in operation.

Carency appeared to us as a very muddy little place. Rebuilt, of course, on the same lines as before the war.

From Carency we cut across the country to Vimy Ridge. Six hundred acres along the crest have been given as a memorial to the Canadians. Our government is building a very fine driveway along it, and thousands of young pines have been planted between the Ridge proper and the old line of mine craters, just east of Neuville St. Vaast. Most of the war debris has been cleared away though in the woods near La Folie Farm, a few belts of wire entanglement may still be found. The ??? and trenches are untouched even by the treasure hunters. We did see one lone digger who looked very sheepish as we came up, so perhaps brass-mining is forbidden in this section. We found two or three small cemeteries on the Ridge, but I understand most of those who fell at the taking of the Ridge were buried at Mont St. Eloi.

Evening was closing down as we sought hospitality at Thelus. Far to the north the French memorial at Notre Dame de Lorette winked its light over the intervening miles. Its flame commemorates the 50,000 French dead who fell while trying to take those heights in May, 1915. You will remember when we took over that sector one year later, their dead still lay along every old trench. Their skeletons were far more plentiful than were the scattered groups of buffalo bones that dotted the prairie in the old homesteading days.

The village of Thelus still wanders along the roadside for a quarter of a mile or so. I was surprised at its size. Up until our visit I always remembered Thelus as a cross-roads with a few little piles of brick rubble.

Neuville St. Vaast has lost its whiteness. Very few houses have been built of the beautiful chalk that formerly gave the town its distinctive appearance. Do you remember the highly-colored stories about Neuville, whispered to us by the old crones in rival towns? Libellous or true, red is now the prevailing color scheme in the resurrected Neuville.

We did not go back as far as Mont St. Eloi, though the ruins of the old monastery still show up as plain as ever.

From Neuville we struck across country towards the east. Over that old crater line I once suffered, among a lot of other things, whooping cough. When I started to cough my fellow warriors would duck for cover. A chap on the other edge of the crater, who evidently was interested in my case, would kindly throw over a couple of “pills,” with the intention of landing them in my midst and effecting a permanent cure. Eh bien! As one might say. The cough has gone; the pill-thrower, too, and only the craters remain!

Then on to the crest of Vimy Ridge, crossing our path of the previous evening. Advancing single file where the going was very rough and anon open order, following the path my old regiment took one morning through a snow-storm, stubbing our toes on wiring irons, stopping now and then to deliver a lecture on Stokes mortars or the danger that lies in innocent-looking whiz-bang duds. On the way one of the Grave Commission men was telling me there have been about 300 fatal casualties in the Ypres section since the war. Even yet there are two or three a month.

The ruins of La Folie Farm are untouched. Here we stopped to rest a while. In the woods nearby can still be seen a veteran or two of pre war woodland days. Their gaunt, bare stumps still overlook the swift growing young life. A bird twittered nearby and the winter sun shone weakly down on that scene of terrific endeavour and glorious achievement. (That last bit is permissible, Buddy, because I was not with the first wave that morning.)

Under the hill toward Vimy town I showed Mrs. F. J. [his wife Jean], the old German gun-pits where Fritz left his howitzers and retreated for several miles while we sat on the Ridge “consolidating” our gains. I pointed out where he – Fritz – of course, dug in again beyond Avion and then returned for the guns that we had been looking after for him.

La Chaudiere looks very busy though many of the dwellings here are temporary – you know, old army huts and sheet iron shelters. The cemetery here is a credit, well kept up and practically completed. In fact all the cemeteries that are finished look great. The wooden crosses have nearly all been replaced by headstones cut out of hard English sandstone. In every cemetery is a list of the graves and also a visitor’s book. In several of the latter we discovered in a very bold hand the name “Gen. Sir Arthur Currie!” Each time I saw it I felt an almost uncontrollable itch to inscribe my own. “Mr. Pte. F. J. Whiting, Esq., Rear Rank!” However, my better half, who is a conservative by nature if not politically, persuaded me against that indulgence.

After lunching at Vimy we caught a train to Arras. When we arrived it was raining, and as we did not wish to waste any time we spread ourselves to a taxi which took us around the battlefield to the east. My chief objective was a certain spot between Monchy and Pelves, where once on a time my trotting powers were put to the test and found wanting. [Monchy-Le-Preux. One of the key positions in the Arras sector, alternately occupied by British and German forces. Mr. Whiting was here taken prisoner in one of the German counter-attacks that followed the final capture of the Monchy Heights by the Third Canadian Division, in August, 1918. This explains his reference in the story about his powers of running put to the test and found wanting.] Unfortunately, I could not get my bearings. I could not even locate where we jumped off, nor was I quite sure which wooded hillside held us up with machine guns, nor which hill it was where Fritz massed for a counter-attack.

We visited several cemeteries but found very few Princess Pats – in fact as we turned back towards Arras my wife gave it as her opinion that that regiment could not have seen much scrapping!

From Arras we took the train to Albert and walked out to Pozieres. Not a trace now remains of those hundreds of guns that stood wheel to wheel, battery after battery by the side of that highway. I remember tottering along that road about nine o’clock on the morning of September 17, 1916. We had made quite an advance on the 15th, and Fritz was shelling the road all the time. Gangs of men were at work repairing it where the shellfire was doing the most damage. At one place it was so hectic that two men who had been killed had not been removed, and they had been built into the road. I could see their shoulders and hips just peeping through the broken stone.

On the crest of the ridge that overlooks Courcelette is a very fine monument to the Tank corps. This, of course, was the spot where the tanks made their debut into the war. A little way past the memorial and the old Sugar Factory, we turned off to the left down the Sunken Road. It is only used as a sheep path now. The photo gives a little idea of what it looks like. Steel helmets, British and German gas masks, rifles, bones, dud shells and other war debris is found all along.

Courcelette is practically as good as new again. To the north-west one notices at once the large cemetery. It lies exactly over the spot where all during the night of the 7th and 8th of October, 1917, I shivered with fright in a dug-out, waiting for the zero hour. Ten to three, I believe it was, but it was probably later. In fact those very dug-outs are giving the graves people considerable concern just now. They have started to cave in and upset the scheme of things up above. An ancient, armed with a hazel twig, has been employed to locate the whereabouts and ramifications, and when we were there work had just started at the supposed entrances with the object of opening them up and filling them in.

Over the hill Regina Trench! There, for some reason, several quite large tracts of country lie very much as it used to be. We caught a train at Miraumont and journeyed down to Boves. I went to revisit the Bois de Boves from where we jumped off on the morning of August 8, 1918. Luck was out. There were two Bois de Boves and I found neither. All one morning we wandered around but I could not get my bearings, so we finally gave it up and went down to Paris.

To those interested I might add that the Faubourg de Montmartre is still as glittery as ever! The jolly old Moulin Rouge, Folies Bergere and the Casino de Paris, are still flourishing, though the opinion of nice French people – and I am not sure they are wrong – is that places like the Chat Noir, Rat Mort, Cabaret de l’Enfer and others, are run specially to entertain the tourists.

Truly the French and Belgians have performed wonders in the comparatively short time since the armistice. To be sure they counted on the Germans footing the ultimate reckoning all the time the reconstruction boom was at its height. That hope has suffered a heavy knock on the head, with the result that the franc is not as popular as it used to be. The value of the franc seems to adjust itself to the French, and, as far as possible, the French readjust it for the tourist.

I know, Buddy, that you’ll say the above is a fair sample of my economics. It will recall to you the time when Shaky Ford used to discuss learnedly of economics in the old Tottenham Tunnel, under Vimy, and you and I used to start discussions on the right of a king to kick a woman in the jaw, or some other subject of equal importance in order to shut him up. But with all your contempt for my economies I’ll risk the opinion that France seems economically sound. There is practically no unemployment. The farmers are all doing well. The shopkeepers complain most because they felt that taxation falls heaviest on them.

In closing I will report on those of your old friends I was able to find. Celestine got tired of waiting for you and now has three little lace-makers that speak her own inimitable patois. Eloise, likewise, has chosen the humble reality of a miner’s cottage for the shadowy promises which seem to have passed between you. Francine has gone to Australia. Nada, alone (and, by the way, she is grown surprising fat), sends her undiminished love. Cheerio, Frank