SSNS Home > Senior Years > Curricula 9-12 > Grade 11 > Canadian History > Battlefields Tour > 23 July 2010

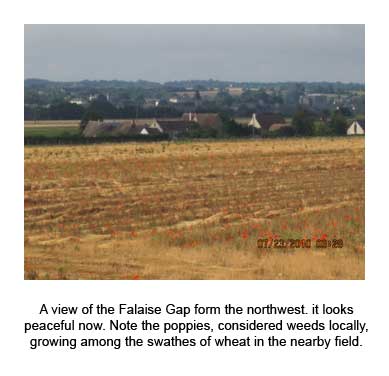

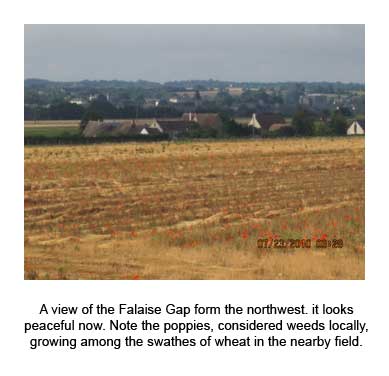

This was the last day of our tour. Today our focus was Operation Tractable, which was the allied effort to prevent the defeated enemy from escaping through the “Falaise Gap”. After breakfast, we drove southeast of Caen and stopped next to a field somewhere in the vicinity of Bretteville-le-Rabet and Verrières northwest of Falaise. Lee started out by orienting us to the geography of the area. We could see Mount Ormel in the distance to our left, the Dives River Valley below us, and Falaise off to the right. Lee then gave us a summary of the situation leading up to Operation Tractable on 14 August 1944.

The Germans were in trouble. They had lost many tanks in Operation Totalize, and they only had about 5,000 of their soldiers left of the 20,000 that had been in that area. The Canadians were tired by this time, having had no rest from the 6 June until 14 August 1944. They had been steadily moving eastward along a stair-step terrain and the ridge to the left ahead of them was the “last of the stairs” controlled by the Germans. To the right was another ridge also in German hands, but under pressure from the advancing Americans to the south. In between these two ridges was a lower-lying area through which the Laize, Laison, and Dives rivers flowed. This was the route that the retreating Germans could use to escape. Since Falaise was the main town at the eastern end of this route, it became known as the “Falaise Gap”. The Allies aimed to close this gap and prevent the escape, not only of the 5,000 remaining enemy soldiers defending this area, but also those who were being pushed east by the advancing Allied forces in other areas of Northwest France. If Operation Tractable succeeded, it would force the surrender of tens of thousands of German soldiers and greatly reduce Germany’s capacity to continue the war.

The task of the Canadian and Polish troops was to move in from the northwest and capture Falaise, then connect with the American forces coming in from the south. To prevent this, the Germans poured in fresh troops, which meant that the tired Canadians and Poles had to face rested, well trained, private soldiers. They did the job, but were criticised for not doing it fast enough to prevent 40,000 German troops from escaping.

As Lee pointed out in their defence, Canadian forces had little help from the Americans, who decided not to move down into the valley, because they had been decimated in previous such battles in Tunisia and Sicily (Salerno). Montgomery also did not commit British troops to the drive on Falaise. We were three weakened Canadian divisions against four weakened German divisions, who were falling back, when fresh German troops arrived. These new troops were supposed to press west and attack the Americans, but they had to stop between Mount Ormel and Falaise to help the four divisions under pressure.

By this time, there was mass confusion everywhere in the German lines. Morale was low, and they were giving up and fleeing their posts. The rest were so desperate to escape that they moved even during the day, and Allied bombers created havoc among them. It was mass confusion everywhere. Roads were crowded. Eighty percent of the German army was still horse drawn in 1944, as Germany didn’t have enough manufacturing to support more than twenty percent of its army. So they ran, and 40,000 soldiers were able to get through the Gap before it closed, leaving 200,000 soldiers behind, either dead, wounded, or captured.

It would take several months before Germany would build up its strength again, by recruiting its tradesmen, teachers, etc., who had previously kept the German infrastructure going. The Russians were at Warsaw; there was a big push in Italy. Germany was breaking down civilly. There were plots against Hitler, and the German resistance was growing. All the while the crematoriums were doing their evil work. More Jews were exterminated between D-Day and Falaise than at any time prior to that, so it was urgent to end the war as soon as possible.

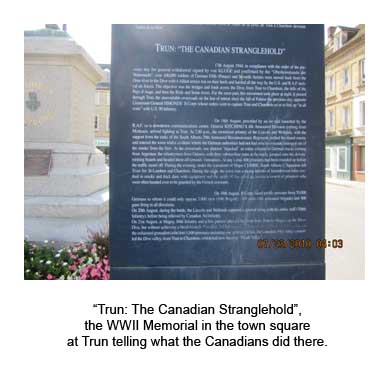

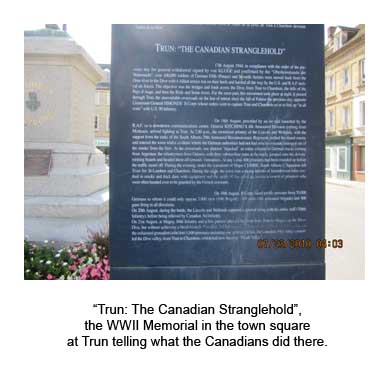

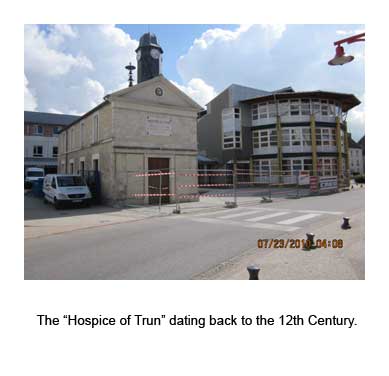

After Lee’s orientation, we travelled through a number of villages, including Crocy and Fontaine les Bassets to the town of Trun. We stopped for a break in the square and took pictures. A reporter from a local newspaper noticed us and came over to interview Lee about the tour. With Laura’s assistance, Lee was able to explain our purpose, and before we left we had our picture taken. We’d made it into the papers!

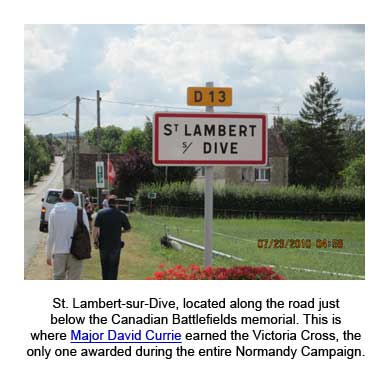

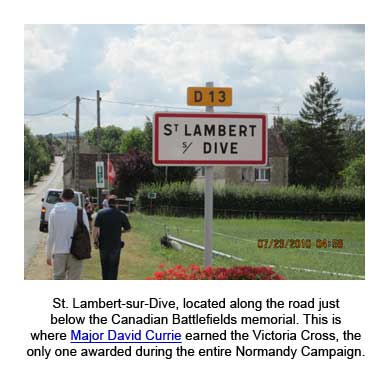

From there we went along the road leading to Chambois. It was between these two points that the fleeing German troops made their escape. Our first stop was at a Canadian Battlefields Memorial on the rise above St. Lambert-sur-Dives. Lee explained that the Canadian and Polish troops were spread thinly in the villages and uplands up to this point. Consequently, when Major David Currie and men from the 4th Division arrived here on 18 August 1944, they were few in number. They met some resistance, but the Poles above them were able to prevent the fresh troops from attacking from that direction. Positioning themselves above the fleeing Germans, St. Lambert became a killing field of monumental proportions. It was no easy battle. The Germans were fighting a desperate tactical battle under fire. Currie only had two hundred men at the last, but they did their job so well under his calm, encouraging leadership that many Germans simply surrendered. The gap was closed at this point, but unfortunately Canadian forces were unable to complete the job before the remaining Germans escaped. For film on the Battle at St. Lambert-sur-Dives, see “23rd Field Regiment RCA - Episode 1, Part 44, Battle of Normandy”.

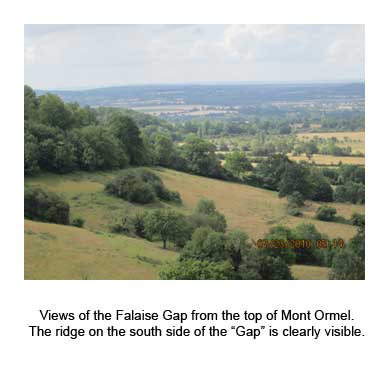

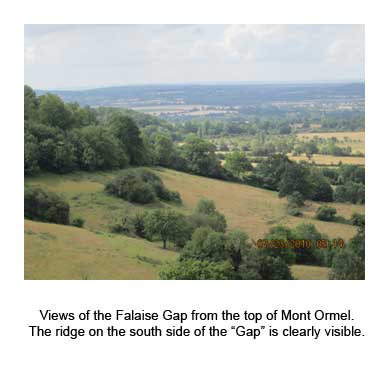

We passed through Chambois with its 12th Century Norman Keep, which had a WWII monument in front of it. It was here that the Polish and American forces closed the gap on 19 August 1944. We did not stop at Chambois, but drove up the ridge to Mont Ormel and the memorial to the Polish Armoured Division. There is a splendid view of the surrounding landscape from this ridge, and it is easy to see why it was of such strategic importance to both the German and Allied forces. We had our last seminar of the tour at this beautiful spot.

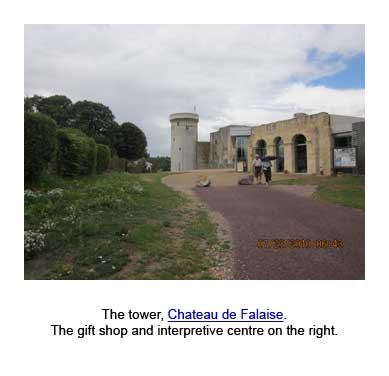

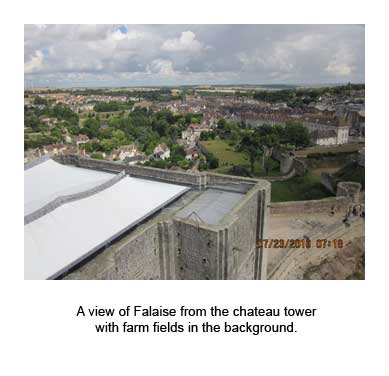

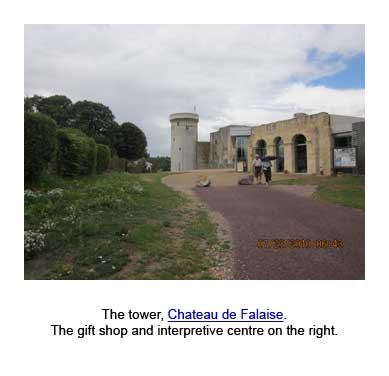

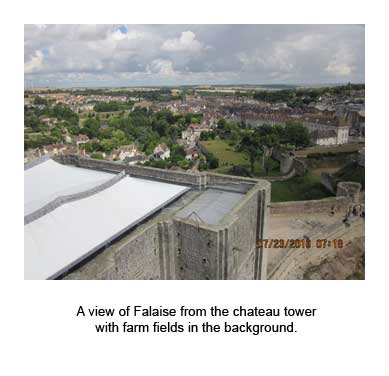

We drove from here to Falaise via Chambois, and a few other villages, like Fresne la Mère and Le Pont de Villy. We had a couple of hours to look around. Most of us visited the Château de Falaise, the ancient seat of the Dukes of Normandy, still in good repair after the ravages of war, both old and more recent. When I passed through the rooms of the keep, I couldn’t help but think how cold they must have been for our ancestors. Even our poorest people today live better than kings eight hundred years ago.

We then returned to Vaucelles and made our preparations for an early start in the morning. We were going to Paris, most to fly home to Canada, but for three of us, our tour was still not over.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|